When you’re first learning to code, the emphasis is often on functionality and making your code do what you want it to. But once your code “works”, are you really finished? This is the point that it’s good to start thinking about Anti-Patterns. Learning how to avoid Anti-Patterns is an easy way to level up your code: it will be easier to understand (Readability!), easier to extend and add new features to (Extensibility!), and will be easier to fix bugs in once it’s been released (Maintainability!).

When I started my first job in tech three years ago, I had very little programming experience - I’ve since learned Java, both on-the-job and from my further research, and believe that it’s never too early to start thinking beyond simply writing “functioning” code. Since I’m now the Product Owner on an L3 Support team (which handles the technical, code-level support and bug-fixing for a Java product once it’s been deployed to the field), I’m particularly invested in encouraging people to think about how they can make the code they write more Maintainable. This blog post covers three common Anti-Patterns that I’ve seen, including details of how you can identify and fix them in your code.

So what is an Anti-Pattern? In Software Development, a Design Pattern is a generic, re-usable template that you can follow to build a solution to a common problem. Conversely, an Anti Pattern is a design, solution, or implementation that ends up being counter-productive. I found it useful to think of them as bad habits - things that you do in common situations that initially seem to “work”, but often have a range of bad outcomes or unintended consequences.

Anti-Pattern 1: Magic Numbers and Strings

A magic number or string is an unexplained or unnamed number or string literal variable in your code.

Integer myResult = myIntegerInput * 24 * 299792 * 60 * 60;

Magic Numbers and Strings are a bad idea, as they can be very detrimental to the readability of your code - that is, the make it a lot more difficult to work out what is going on simply by looking at the source code, as there would be work involved in figuring out why a number is used, or where a string comes from. It also makes your code difficult to support if the source or purpose of the number/string isn’t documented anywhere. Changing the value of the number means you need to change it everywhere it’s used - that takes more time than if it was just defined in a single variable, so is more expensive, and also opens up the possibility that you could miss some of the instances, and thus introduce bugs into the code.

Luckily, it’s easy to get rid of Magic Numbers from your code! You should define any strings or numbers in their own variables, with good variable names, and comments to add an extra explanation if necessary. If you have numbers, it’s also important to include the units - if you have a variable that’s called loop_time, it might not be obvious if it is measured in seconds or minutes or hours.

// The speed of light in a vacuum in km/s

Integer speedOfLight = 299792;

Integer secondsInDay = 60 * 60 * 24;

Integer totalKilometres = numberOfDays * secondsInDay * speedOfLight;

Anti-Pattern 2: Lasagna code

Lasagna code is code with too many layers. In Java code, its exemplified by large inheritance chains. For example, the longest inheritance chain I found in one codebase I’ve supported was 7 classes long (6 “extends”) and the longest in another codebase was 4. Guess which one I find it simpler to follow the code path through!

Codebases like this are difficult to work in - they are less supportable, as tracking down bugs is like navigating a labyrinth, and adding new features is more complicated, as you need to work out where in the hierarchy they should go and how the changes will interact with the subclasses. Testing changes to classes higher up in the inheritance chain means you might need to retest everything involved, which is expensive, especially if there are lots of bottom-level subclasses.

Fundamentally, my advice would be to never design any new code like this. It’s often a sign of trying to generalize code too early, making it unnecessarily more complicated. An experienced engineer once gave me the advice that your code should follow the YAGNI (You aren’t gonna need it) principle, including any generalization - that means that you don’t need to add functionality (in this case the abstraction of inheritance) until you actually need it. If you’re writing a “generic” superclass that’s only used by one subclass, then you don’t need it! If you already have a codebase that’s designed like this, it’s worth thinking about whether you should be doing a redesign - does everything really need to be linked via inheritance? Could you avoid unnecessary inheritance by separating unrelated bits of function, or using composition of classes instead?

Anti-Pattern 3: God Class

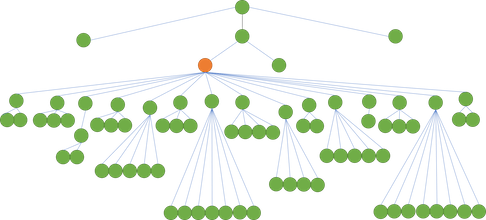

This Anti-Pattern means that you have one “God” class that is referenced by all the other areas of the code and contains all the information (for example constants or methods to pull in data from external sources) and the functionality required for processing the data.

Again, this Anti-Pattern makes your code less readable, as each sub-section of code will probably only require some of the data and functionality contained in the “God” class, but it will be difficult to see without further investigation what it actually uses. As all the functionality is concentrated in one place, maintaining the code is more difficult, as any changes to the “God” class could potentially impact every other bit of the code. That means fixing and testing the code is more complicated, risky, and time-consuming, and that combination always leads to more bugs.

To improve a codebase with a “God Class”, you would split out the bits of functionality into smaller, more concise classes, which would be linked via composition - each bit of function only needs to have access to the data and methods that it uses. For example, instead of having a single “God” class Car containing all of the function, you could have a Car class that holds a reference to an Engine class and a Seat class, which holds references to a Seatbelt class and a Headrest, and so on.

What Next?

The three Anti-Patterns I’ve covered above just scratches the surface of the wealth of information that’s available on this topic. If you’re interested in learning more about Anti-Patterns (which you should be - there’s an entire list of pasta themed Anti-Patterns!), then there are lots of resources available online. If you’re looking for a textbook on Java, I would personally recommend “Effective Java” by Joshua Bloch, which is what I’ve used during my first few years of learning to code.